In January of 2001, I watched a grainy pirate copy of Castaway,

starring Tom Hanks. If you haven't seen it, it is about a guy who

gets stranded on a desert island and has to learn how to survive.

In January of 2001, I watched a grainy pirate copy of Castaway,

starring Tom Hanks. If you haven't seen it, it is about a guy who

gets stranded on a desert island and has to learn how to survive.

My favorite part of the movie is right after his plane goes down, when he is in the water with the airplane.

My second favorite part is where he makes fire without matches. He tries with great effort to make fire after he realizes a signal is essential to his survival. He makes it look hard, and I was forced to wonder, just how hard is it to make fire without matches?

Tom

Hanks is pretty damn happy to succeed. This is the kind of triumph

over the elements that I was looking forward to.

Tom

Hanks is pretty damn happy to succeed. This is the kind of triumph

over the elements that I was looking forward to. I put the project off until late July, when I was reminded of it by

Becky's house fire. It was Saturday, so I had the whole weekend to

try. I tried to place myself in Tom's character's situation: On an

island with a knife and trees. Ok, so Tom didn't have a knife, but

eventually he made one, so I allowed myself that.

I put the project off until late July, when I was reminded of it by

Becky's house fire. It was Saturday, so I had the whole weekend to

try. I tried to place myself in Tom's character's situation: On an

island with a knife and trees. Ok, so Tom didn't have a knife, but

eventually he made one, so I allowed myself that.

I also decided to refrain from looking up instructions on the internet, assuming I was not stuck on an i-land.

I went to the nearby park, which is the park with Sutter's Fort in it,

and collected a few sticks and some kindling.

I went to the nearby park, which is the park with Sutter's Fort in it,

and collected a few sticks and some kindling.

I prepared two 5-gallon buckets of water, standing by in case the fire got out of hand. The day was very hot, and after seeing Becky's blackened house, I decided not to take any chances.

This turned out to be extremely optimistic.

I

prepared a big bundle of tiny, crisp tinder, sharpened one stick a bit and

started rubbing. I kept the bottom one (I'll call it the skid-plate)

steady with one foot and sawed at it with the other stick. I was

operating in the full Sacramento sun because I wanted to take advantage of

the hot sunlight. Everything around me felt very dry.

I

prepared a big bundle of tiny, crisp tinder, sharpened one stick a bit and

started rubbing. I kept the bottom one (I'll call it the skid-plate)

steady with one foot and sawed at it with the other stick. I was

operating in the full Sacramento sun because I wanted to take advantage of

the hot sunlight. Everything around me felt very dry.

After about 50 strokes, the friction was great enough to create some smoke, and everything near the action was very hot, but I slowly came to the realization that really hot is not the same thing as on fire. It took a lot of energy to produce that much heat, and the vigorous action of the rubbing kept pushing all of the tinder out of the way, or at least away from the hottest point of the operation.

It is especially hard to make fire when one hand is operating the digital camera.

Sweat ran down my face and arms. I had to avoid having it drip right onto the bottom stick, extinguishing my effort.

My downstairs neighbor Jennifer came home and caught me at work. I told her what I was up to and she expressed a small amount of admiration and confusion. She also pointed out that the humidity on Tom's island was a lot higher than here, and that gave me an unfair advantage.

I rubbed some more. It was tiring.

After about an hour, I realized that there was something wrong with my technique. Where did the actual flames come from? I was pretty tired, but the blackened ridge down the skid plate was somewhat redeeming. I quit for the day and went upstairs to my air-conditioned room.

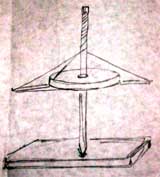

Mike

drew a sketch of a reciprocating drill that spun an upright stick down

into a slab of wood. This looked mildly promising and I was certainly

ready to try a little less elbow grease and a little more engineering.

Mike

drew a sketch of a reciprocating drill that spun an upright stick down

into a slab of wood. This looked mildly promising and I was certainly

ready to try a little less elbow grease and a little more engineering.

I was pretty sure I would succeed tomorrow.

The next day was Sunday. I went back to the park to get more kindling and some straight sticks for building the reciprocating drill. The nearby park is also the home of Sutter's Fort and the California State Indian Museum.

In an amazing stroke of luck, Ranger Joanne happened to be standing outside of the museum, saw me examining sticks, and asked me what I was up to.

"Did you ever see that movie Castaway with Tom Hanks?" I asked.

She had. She told me that they teach kids about lighting a fire the way the Indians did, by twirling a stick down into a little hole.

She

told me that the kids try and try to light a fire, even to the point of

getting blisters on their hands, but they usually lack the muscle required

to get a fire started. She also showed me that with two people,

twirling down the stick at the same time, how a constant point of attack

could be maintained at the base of the stick. she showed me how a small

notch should be cut next to the hole, to allow the hot sawdust to fall to

a delicate clump.

She

told me that the kids try and try to light a fire, even to the point of

getting blisters on their hands, but they usually lack the muscle required

to get a fire started. She also showed me that with two people,

twirling down the stick at the same time, how a constant point of attack

could be maintained at the base of the stick. she showed me how a small

notch should be cut next to the hole, to allow the hot sawdust to fall to

a delicate clump.

Unfortunately, I was stuck on my island alone. I didn't even have a photographer to help me.

She ushered me into the museum and showed me a photo of Ishi starting a fire between his two hands. She also showed me a plank that had been used in the fire-starting process. She took me into the "backyard" of the museum and showed me a stack of drying cedar bark and some willow branches. She handed me a straight, 12 foot branch of willow and some cedar bark. She suggested I try lint as kindling also.

This was really awesome. This was my first time "backstage" at a museum. I was getting pretty confident about the fire making attempt to come.

Here

she is with the fallen cedar. She also instructed me to visit a

hardware store and buy a cedar shingle to use as a base-plate.

Here

she is with the fallen cedar. She also instructed me to visit a

hardware store and buy a cedar shingle to use as a base-plate.

Can you spot her firearm?

As we were leaving the museum, we passed by the tiny museum store. Inside the case was a little reciprocating drill, with the same features that Mike had drawn the night before. I made mental notes of it's attributes.

With

my new cache of building materials, My first approach was to start building my drill.

I was afraid that the string would just unwind and not re-wind back up the

pipe, and as it turned out, that was exactly the problem I started running

into.

With

my new cache of building materials, My first approach was to start building my drill.

I was afraid that the string would just unwind and not re-wind back up the

pipe, and as it turned out, that was exactly the problem I started running

into.

I also tried twirling the sting between my two hands, but they quickly became chafed and I could tell that the time it took to reposition my hands was allowing the heat to dissipate.

This wasn't going to work.

It

felt as though I was concentrating my efforts on a smaller area, a tiny

dot the size of a screw-head was being subjected to a lot of pressure and

effort, but I couldn't even make a little smoke. This technique was

also a lot more controlled down where the contact was being made, so I

could more carefully position the tinder, and the cedar tinder was so dry

and desiccated, it seemed absolutely poised to burst into flames.

It

felt as though I was concentrating my efforts on a smaller area, a tiny

dot the size of a screw-head was being subjected to a lot of pressure and

effort, but I couldn't even make a little smoke. This technique was

also a lot more controlled down where the contact was being made, so I

could more carefully position the tinder, and the cedar tinder was so dry

and desiccated, it seemed absolutely poised to burst into flames. After

my hands were tired, I decided to test the twirling stick approach by

chucking-up the twirling stick into my Makita cordless drill. I

wanted to gauge just how fast and powerful my little hands would have to

work to start a fire. Unfortunately, both of my 9.6 volt batteries were

dead, and seemed to not want to take a charge, so this idea didn't

really get anywhere.

After

my hands were tired, I decided to test the twirling stick approach by

chucking-up the twirling stick into my Makita cordless drill. I

wanted to gauge just how fast and powerful my little hands would have to

work to start a fire. Unfortunately, both of my 9.6 volt batteries were

dead, and seemed to not want to take a charge, so this idea didn't

really get anywhere.

I also began to question if the willow branch I had gotten was really dry enough. It was a little too flexible too.

Maybe I was just running out of patience.

Before I quit for the day, I tried a few more times to use the Tom Hanks

patented chiseling method. Hot ridges and smoke were pretty easy to

obtain using this method, but everything was moving around again, and it

was impossible to keep the kindling from vibrating all over the

place.

Before I quit for the day, I tried a few more times to use the Tom Hanks

patented chiseling method. Hot ridges and smoke were pretty easy to

obtain using this method, but everything was moving around again, and it

was impossible to keep the kindling from vibrating all over the

place.  My

chisel-stick started to break, so I called it a night. I was really

hot and tired and discouraged.

My

chisel-stick started to break, so I called it a night. I was really

hot and tired and discouraged.

One of the problems with trying to start a fire without matches is that everyone has an idea of how to do it. Everyone has either seen a diagram, or an educational film, or watched a Powerpoint presentation, or seen an animatronic Indian do it, but hardly anyone has actually sat down and done it.

I was starting to get advice from everyone about what I should try and what I might be doing wrong. I don't usually get myself into situations where everyone is giving me advice, and I didn't like it much. Of course, they were just trying to help. So now, writing this, I would like to apologize for being such a punk about it. I am sorry.

That night I decided to go where I could find out more on the American Indian and his lifestyle: The Cache Creek Indian Gaming casino.Just kidding. I went online and started poking around. The best site was David Little's Aussie Fire Bow. His informative site was so funny that I almost didn't bother writing one myself.

The majority of websites recommended a bow and spindle arrangement, and this seemed like a worthwhile approach to me, so I decided to try this method after work on Monday. I was pretty sure I would succeed tomorrow.

On

Monday after work, I tried again. I found a

branch with a fork on it and strung some natural fiber rope around it to

make a bow. I also pressed a bottlecap into a piece of cork to make

a socket for the top of the spindle. On an island I assume I could find a

shell and a knot of wood somewhere to serve this purpose.

On

Monday after work, I tried again. I found a

branch with a fork on it and strung some natural fiber rope around it to

make a bow. I also pressed a bottlecap into a piece of cork to make

a socket for the top of the spindle. On an island I assume I could find a

shell and a knot of wood somewhere to serve this purpose.

I finally started working in the shade. I realized there was no point in exhausting myself in the direct sunlight if it was only going to benefit me 15 degrees or so. I also placed the entire operation on the stairs so that I was only half-squatting. This was much more comfortable.

It took a couple of tries to get the rope tight enough to wrap around the stick one time and still be taut.

I was able to get the spindle stick turning sometimes, but it would also

slide around the stick without moving it sometimes. The spindle

would just bend sometimes, especially if the rope was too high on the

stick. The bowing motion had to be very smooth or something would catch,

and the operation would halt.

I was able to get the spindle stick turning sometimes, but it would also

slide around the stick without moving it sometimes. The spindle

would just bend sometimes, especially if the rope was too high on the

stick. The bowing motion had to be very smooth or something would catch,

and the operation would halt.

A cellist might have an advantage here.

I used the fingers on my sawing hand to adjust the tension on the rope, but it wasn't much help.

The

fibers in the rope gave out after about 20 minutes of abuse. I had

made a little black hole and a little bit of smoke.

The

fibers in the rope gave out after about 20 minutes of abuse. I had

made a little black hole and a little bit of smoke.

I found some thicker cotton cord and tried it again. On the island I would use my shoelaces for this operation, or maybe leather.

Here

is a photo of Mike giving it a try with his "stranded" beard. He

sure gets into these little projects!

Here

is a photo of Mike giving it a try with his "stranded" beard. He

sure gets into these little projects!

Watching Mike

sawing hard, I was afraid he would break the spindle. I warned him that I

would kill him if he broke the spindle now, on the brink of my

success. This bending spindle finally caught my eye as a serious

problem. Joanne the ranger had given me a green branch, but I hadn't

realized it at the time.

Watching Mike

sawing hard, I was afraid he would break the spindle. I warned him that I

would kill him if he broke the spindle now, on the brink of my

success. This bending spindle finally caught my eye as a serious

problem. Joanne the ranger had given me a green branch, but I hadn't

realized it at the time.  I

recommend wrapping the rope so that the high-end of the rope is on the

side close to you.

I

recommend wrapping the rope so that the high-end of the rope is on the

side close to you. Here

is a close-up of the bottlecap and cork I used at the top of the spindle.

Eventually I put some oil on it to lubricate it so it wouldn't be

uncomfortably hot.

Here

is a close-up of the bottlecap and cork I used at the top of the spindle.

Eventually I put some oil on it to lubricate it so it wouldn't be

uncomfortably hot. The new rope was better, but the spindle was too flexible. When I got a

little smoke, I would start bowing faster and it would always start to

bend and get too wobbly.

The new rope was better, but the spindle was too flexible. When I got a

little smoke, I would start bowing faster and it would always start to

bend and get too wobbly.

I

did manage to spin all the way though my base-board and drill a little

black hole into the stairs.

I

did manage to spin all the way though my base-board and drill a little

black hole into the stairs. Here

I set up a second board as a tinder-holder and backup.

Here

I set up a second board as a tinder-holder and backup. Mike

snapped a shot of my frustration here. See how my fingers are poised

around the bottlecap? It got pretty warm.

Mike

snapped a shot of my frustration here. See how my fingers are poised

around the bottlecap? It got pretty warm.

It was getting dark, so I gave up for the day. This this new method was showing great promise. I decided that I would give up on Joanne the Ranger's willow branch and find something a little straighter, dryer and fatter.

My dad came over later that evening and listened to my progress. He thought it was pretty funny that I quit when it got dark.

I

needed a straight stick, but in the world of sticks, straight is relative.

On Tuesday after work, I double-checked under every tree at Sutter's

fort, but nothing was looking very promising.

I

needed a straight stick, but in the world of sticks, straight is relative.

On Tuesday after work, I double-checked under every tree at Sutter's

fort, but nothing was looking very promising. Here

is another stick. It is straightish, but it wasn't exactly perfect.

It also seemed too flexible. Straight and thick was a somewhat rare

combination.

Here

is another stick. It is straightish, but it wasn't exactly perfect.

It also seemed too flexible. Straight and thick was a somewhat rare

combination. I

eventually got in my car and made a trip down to the river. the closest

access to a river from my house is the overpass at 16th street near the

Blue Diamond Almond factory. This particular area is in a somewhat

seedy part of downtown, where homeless people camp and cross into Del Paso

Heights. I was alone and feeling kind of creeped out, but when you

are on a quest for a straight piece of willow, the riverside is exactly

where you want to go.

I

eventually got in my car and made a trip down to the river. the closest

access to a river from my house is the overpass at 16th street near the

Blue Diamond Almond factory. This particular area is in a somewhat

seedy part of downtown, where homeless people camp and cross into Del Paso

Heights. I was alone and feeling kind of creeped out, but when you

are on a quest for a straight piece of willow, the riverside is exactly

where you want to go.

Here is a photo of some homeless-generated trash...and sticks!

Within

15 minutes, I had found three damn straight sticks. Look at these babies!

There was a spring in my step again. The dark one was particularly

promising.

Within

15 minutes, I had found three damn straight sticks. Look at these babies!

There was a spring in my step again. The dark one was particularly

promising. Here is a photo of the dark stick. It is dry and straight and about 1/2

inch thick (13 mm). When I dropped it, it clicked like a

drumstick. I trimmed it to 16 inches long, and then cut it down

again to the straightest 13 inches. It wasn't perfectly

straight, but it was much better than what I had been working with. the

top end of it is rounded off for the bottle-cap, and the bottom is flat

where it touches the base-plate.

Here is a photo of the dark stick. It is dry and straight and about 1/2

inch thick (13 mm). When I dropped it, it clicked like a

drumstick. I trimmed it to 16 inches long, and then cut it down

again to the straightest 13 inches. It wasn't perfectly

straight, but it was much better than what I had been working with. the

top end of it is rounded off for the bottle-cap, and the bottom is flat

where it touches the base-plate.  I

recommend using a knife to carve a shallow pit (two millimeters

deep) into the baseboard for the spindle to sit in. Carve it about a

quarter-inch from the side edge of the baseboard. In this photo you can

see four of them in a row.

I

recommend using a knife to carve a shallow pit (two millimeters

deep) into the baseboard for the spindle to sit in. Carve it about a

quarter-inch from the side edge of the baseboard. In this photo you can

see four of them in a row.

Before you start spinning with the bow, twirl the stick by hand in the shallow pit until a little indentation is made, then use your knife to cut out a small "v" shaped notch through the thickness of the wood. This small channel is to allow hot sawdust to fall into a small pile that will theoretically start to smoulder.

After all those set-up steps are taken, you can begin in earnest with the bow.

The rope was stretched out enough to be very snug against the bigger stick.

It felt very very promising. Finally the bow would really be able to

dictate the actions of the spindle instead of just influence them.

The rope was stretched out enough to be very snug against the bigger stick.

It felt very very promising. Finally the bow would really be able to

dictate the actions of the spindle instead of just influence them.

I was confident I would succeed, and I prepared some more kindling for the giant raging fire I was going to soon have.

On

the first try, the bottlecap was hot! Promising...ok, annoying.

On

the first try, the bottlecap was hot! Promising...ok, annoying.  After a few tries, I settled down and got my top fingers out of the way of

the hot bottlecap. I carved the starter pit a tad deeper so the spindle

wouldn't pop out and started bowing away at it.

After a few tries, I settled down and got my top fingers out of the way of

the hot bottlecap. I carved the starter pit a tad deeper so the spindle

wouldn't pop out and started bowing away at it.

Hot sawdust piled up almost immediately and started to smoke. There were a couple of hitches in the bowing, but the action was easy enough to get it very hot again without too much effort.

Suddenly

I spotted a red ember! I gingerly stopped my bowing and saw it was smoking by itself.

I blew and blew and piled on the kindling. The waiting seemed to do as much as the

blowing, but I got a tiny flame as big as a cat's tongue. Yes! Desperate

for it to burst into flames, I blew too much and the little red ember went slowly out.

Suddenly

I spotted a red ember! I gingerly stopped my bowing and saw it was smoking by itself.

I blew and blew and piled on the kindling. The waiting seemed to do as much as the

blowing, but I got a tiny flame as big as a cat's tongue. Yes! Desperate

for it to burst into flames, I blew too much and the little red ember went slowly out. The smoke had been pouring off the baseboard. About ten cigarettes of smoke indicates near-success.

I tried one more time, got a smaller ember & blew that one out faster.

I was a little too anxious to succeed this time. It is so great to see the smoke still coming up after I stop spinning the

shaft!

I tried one more time, got a smaller ember & blew that one out faster.

I was a little too anxious to succeed this time. It is so great to see the smoke still coming up after I stop spinning the

shaft!

I was excited and disappointed. Here is a photo of the sweat beading off of my forehead and of my stupid grin of success.

I was pretty sure I would succeed tomorrow at making a real fire that lasted.

On

Thursday at lunch I bought a redwood stake to use as my new baseboard. It

was a half-inch thick, so I would have a better shot at making a fire

before grinding all the way though.

On

Thursday at lunch I bought a redwood stake to use as my new baseboard. It

was a half-inch thick, so I would have a better shot at making a fire

before grinding all the way though.

I carefully made a deep pit to start the bowing and got my bottlecap fingers positioned carefully.

I made a little (3.2 megs) movie of the bowing.

I got lots of smoke on the first try. I was really feeling in control.

I

stopped bowing when I had thick curls of smoke. I had learned to let

the ember sit by itself for awhile, waving my hand at it instead of

blowing. I made a little movie (2.3 megs) of the waving

too.

I

stopped bowing when I had thick curls of smoke. I had learned to let

the ember sit by itself for awhile, waving my hand at it instead of

blowing. I made a little movie (2.3 megs) of the waving

too.

I let it sit, I waved at it & I piled tinder on top (to warm it up), being careful not to smother it.

Finally,

about 2 minutes after I had stopped bowing, the tinder caught fire!

Finally,

about 2 minutes after I had stopped bowing, the tinder caught fire!

Success!

Here

is another photo of my little fire!

Here

is another photo of my little fire! I

did it! Hoorah! Firemaster!

I

did it! Hoorah! Firemaster!

Bring on the desert islands!

No, that sweat on my forehead is not from the heat of the fire.

My

neighbor was walking by at right this moment & took this photo. The

flame went out & the hot ember dropped into the palm of my hand. Ow. I

just KNEW there was going to be an injury with this project.

My

neighbor was walking by at right this moment & took this photo. The

flame went out & the hot ember dropped into the palm of my hand. Ow. I

just KNEW there was going to be an injury with this project. Here

is a photo of my hand with the first spindle. It ended up being too thin

and crooked. See how you could roll a small pea under it? That means

that it is too crooked and will wobble too much when you spin it.

Here

is a photo of my hand with the first spindle. It ended up being too thin

and crooked. See how you could roll a small pea under it? That means

that it is too crooked and will wobble too much when you spin it. The

top stick of redwood is the one I succeeded with, the two cedar shingles

were too thin and I ended up drilling through them just as the heat was

building.

The

top stick of redwood is the one I succeeded with, the two cedar shingles

were too thin and I ended up drilling through them just as the heat was

building. This

photo shows my successful fire-pit on the right, and a ready-to-spindle

pit on the left.

This

photo shows my successful fire-pit on the right, and a ready-to-spindle

pit on the left.

The secret of making fire with a spindle and baseboard is to grind out a small pile of extremely hot powdery sawdust, which will foster an ember.

The pile of hot sawdust needs to be about the size of the pink eraser on the back of a pencil. Making this little smoldering pile requires the whole violent heat-generation process to be stationary enough to allow a small pile to collect. This is where slow, careful engineering comes in. Also, the graceful touch that comes with practice allows it to happen gently.

Photo

comparison of top stick (failure), and bottom stick (successful).

Photo

comparison of top stick (failure), and bottom stick (successful). In

retrospect, the trouble and anguish that Tom Hanks went through on his

island was actually pretty mild.

In

retrospect, the trouble and anguish that Tom Hanks went through on his

island was actually pretty mild.

My last bit of advice to potential fire makers is that the careful construction of your sticks is very important. If one is too flexible or thick or crumbly, go out and find another one. They won't just save you sweat, they are really the only way to be successful. Good luck!